-- Essays and Articles --

PART ONE: PRELIMINARY DIGRESSIONS & METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

1. DEFINITIONS:

PART ONE: PRELIMINARY DIGRESSIONS & METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

1. DEFINITIONS:

[A] Pharisee -> Jewish ‘Persianizers’: Originally a reform movement within Judaism that accepted Persian (cultural) and Zoroasterian (religious) influence. In 1C an orthodox purity sect.[B] Groups in Diaspora synagogues -> (1) Hellenistic Jews. (2) Proselytes (ie. circumcised and baptised ex-gentiles). (3) 'God-fearers’ and ‘Yahweh-worshipers’. It was this latter group that proved to be the most responsive to the Gospel.

[C] Hellenistic reform-Judaism -> a reform movement within Judaism by those Hellenistic Jews and Proselytes in 1C (eg. Philo) that accepted some aspects of Greek thought and culture. As a result, the name ‘Hellenist’ had the negative sense of Jewish-Paganizers. In Jerusalem many of the ‘followers of Jesus’ sect sprang from this larger group (as did the later hostile reaction to same) to form a daughter church along side the Aramaic mother church started by Peter and ‘the Twelve’; and soon to be headed by Jacob (later 'James') and ‘the pillars’ after 35CE.

[D] Christian -> ‘Messiah worshipers’ (from Antioch c.40CE). Application to pre-70CE ‘followers of Jesus’ highly anachronistic. In one sense Paul was not a 'Christian’ as such, for he spread the Gospel in order to bless all nations according to God's promises to Abraham; hence the ‘brothers’ are Abraham’s children (ie. true Israelites, and true Jews; and not "Christians" as such).

[E] Jewish-Christians -> are those (including both Jews and Gentiles) who practice the (ritual) observance of the Law, and profess faith in Jesus as the promised Messiah. [Before 70CE: the Aramaic churches of Judea and their mother church in Jerusalem under the leadership of Joshua's brother Jacob. The conservative 'circumcision party' was the dominant influence in the Jerusalem church, and among those assemblies loyal to her.]

[F] Jewish-Hellenist Christians [aka JHC] -> Early leaders of these may have included St Stephen and the 'Seven'. In the early-40's this Greek-speaking Church of Jerusalem moved to several of the Empire's major cities (eg. Antioch and Alexandria) as a result of the violent persecution that led to their so-called 'dispersion'. The Gentile 'Christianity' that emerged from this social and religious movement was based on these pre-pauline non-Palestinian converts, and was powerfully charged with Paul's apocalyptic reform-Judaism.

[G] The Time of Waiting -> are those few years between the Ascension and the Parousia: this is the eschatological moment (Spirit filled and prophetic) that characterized the so-called "apostolic age". Paul realized that God's salvific will was "to save the gentiles also before it is too late, to bring the gospel to all heathen people before the end; only then can the end come" (McK 33). Hence the charismatic brotherhood was an eschatological community, a "church of radically new beginnings" (Collins).

2. A Pauline Chronology

[Note: All dates are necessarily approximate]c.10CE Birth of Paulos; youth in Damascus, basic Greek education.25-30 Traveling artisan gains Pharisaic training in Palestine.

33 Crucifixion & Resurrection. Birth of the church in Jerusalem.

31-38 Damascus citizen; Pharisee and persecutor of JHC Church.

36-38 Pilate goes to Rome. Persecution and Dispersion of Hellenists from Judea.

38 Stephen's 'blasphemous' preaching ends in his death by violence via mob 'justice'. Paul's legendary

Apocalypsis or Prophetic call: Paul was sent to preach the gospel to the Gentiles by a revelation or

vision of the Risen Lord, the glory of the Cross, and the need to spread the Good News across the

world. Paulos emerged from 'Arabia' (actually Egypt) having sorted all this out, after leaving Jerusalem

shortly after the lynching of Stephen (an episode symbolizing the expulsion of the radical Hellenistic-

Jewish believers in Jeruasalem).38-39 Paulos goes SW from Judea ... to "Arabia" (ie. Alexandria) with other fleeing JHC . . .

41 The Return to Damascus: his preaching attracts hostile interest, forcing the night escape by

basket. He goes south to Palestine and Judea. The visit with Cephas in Jerusalem (15 days):

they discuss the possibility of future missions, among other things.42-48 Proclamation and mission work in Syria and Cilicia.

48 The so-called 'First Aposolic Council': informal agreement between Cephas, Jacob, John, and

Paul, Barnabas, and Titus settles the circumcision issue, and divides the mission field into two

fields based mostly on geographic and socio-ethnic qualities.48-50 Famine in Judea; Jews expelled from Rome; Temple massacre.

49 Antioch Incident: Peter stops eating with Gentiles; and so Paul rebukes him 'to his face'.

50-52 Macedonian mission begins from Antioch to Galatia to Troy to Philippi to Thessalonika to Athens

to Corinth.50 "humiliation suffered at Philippi" (1T.2:2) Paul, Silvanus, Timothy chased from Philippi to Athens.

Letters A and B co-authored by Paul and Silvanus.51 'Second Council' issues the 'Jerusalem Decree': Food laws and no illicit sex.

Decree-letter sent to Antioch; copies sent to local churches of Syria and Cilicia.52 Paul's 18 months in Corinth completed. Letters C and D co-authored by Paulos and Silvanus.

53-4 Back to Antioch via Jerusalem. Paulos and Silvanus part company before Galatians (2Cor 1:19).

54-8 Mission to Asia Minor and Greece. From Ephesus Paul writes 'Galatians' (in 54);

and four (?) Corinthian letters (54-5); and 'Philemon' (56); and 3 Philippian letters (56-7).60 Last Visit to Jerusalem and Arrest: In jail for his 'crimes', Paul considers the coming conflict between

Judaism & Church, and so was inspired to do what he could to effect rapproachment; hence 'Romans'.62? Death of Paulos; he is last seen on his way to Jerusalem with funds for the poor. Was he lost

to pirates en route? In any case, he passes over into immortality through his literature as his

fame and influence grow; his letters are copied and passed along, and become increasingly

popular with all assemblies and literate believers.65-70 Peter & Mark (in Antioch) collaborate on the first Gospel in response to Paul's writings.

70 the 'Fall of Jerusalem'. City and Temple are destroyed by Roman legions. The first church, the

mother-church, the conserative aramaic messianists are also 'blotted-out'. Any survivors of Rome's

fury would be absorbed by the other churches outside of Judea. It is a crisis-point for both Judaism

and the newly emerging reform-sectarians and apocalyptic messianists named 'christians'.c80 Rabbi's at Jamnia reorient Judaism; establish the Hebrew canon. Rabbinic-Judaism quickly

becomes the norm for all of Judaism. The efforts to convert the Jewish 'people of the book'

are widely recognized as a failure. The future of Christianity lies with the Gentiles after all.

Paulos was right all along! :)85+ Christians expelled from synagogues; the conflict heats up, and the 'parting of the ways' begins.

Gospels of Matthew and John emerge from the ferment with two very different approaches (and in

combination with the on-going dialogue with the first gospel). Silvanus' long-considered letter to all

believers circulates among the Greek churches; and later becomes entitled 'the first epistle of Peter'.

'Hebrews', 'Revelation', and other early christian documents emerge from all areas around the great-

sea. The bare skeleton of what would later become the new-testament is forming slowly but surely

around the two poles of christian prophetic-literature: gospel and epistle ...

3. A NOTE ON DICTION

It is apparent that the usual scholarly treatment of 1&2Thessalonians is, in general, of inferior quality (as compared to the other letters), both from the historical, and the methodological / hermenuetical perspectives. ‘Lukan Lenses’ and various (unfounded) assumptions seriously compromise the integrity of Thessalonian studies. The confusions and misunderstandings that come from simple and easy methodological errors and oversights result in a situation where the significance of seemly innocent, yet very important, words and phrases are missed, or otherwise overlooked. And yet, it is widely acknowledged that when it comes to reading Paul, one can never be too slow or too careful. This is because, with Paul, every word and every phrase holds great potential. Paul’s rhetorical mannerisms (language, style, diction) is very dense and concise; to overlook anything surely does a grave disservice to him. This proposal is largely based on the observation of Paul’s habitual conciseness; and his occasional reticence and indirectness, especially about matters pertaining to himself. One consequence of this stylistic mannerism is that sometimes even the most innocent word or phrase can conceal an amazing weight of meaning.For example, this straightforward statement of fact: "I went away into Arabia" (Gal 1:17) is widely assumed to be mysterious, but is well recognized as being a general and indirect reference to a general direction or area somewhere near Palestine. Of the two alternatives usually proposed, scholars prefer SE to the Nabatean Kingdom / Petra, or rather to its interests near the Damascus area. In doing this the scholars quietly shift attention away from "Arabia" in favor of Damascus (as per Luke), and in essence incorporating Arabia as a small and dependent satellite of Damascus, having no real significance of its own. Not only is this procedure methodologically problematic, but it goes against all that we know about Paul (cf. map). The best option - and indeed the only viable alternative - is south-west from Palestine ... toward Egypt perhaps.

Now this oddly mis-named "Arabia" holds the first place in Paul’s new life, after he received his prophetic call [the legendary Lukan account of which is well known as "Paul’s Damascus Experience"]. Now Paul’s preference for the ‘polis’, and the general direction of ‘Arabia’ (ie. SW of Palestine), suggest Alexandria (and its well-established Jewish presence) as his most likely residence for the year or two that he spent in Egypt [Keeping a low profile? Studying Philo, the Book of Wisdom, and the LXX? Or just awaiting 'the Wrath to come'?] before returning to his home base in Damascus. Perhaps Paul was part of a group of Jewish-Hellenist Christians that were dispersed from Jerusalem to Alexandria around about 35-36CE.

Another good example of this "great weight in words" is 'Athens' (eg. 1T.3:1). Taken out of context, and without reference to Paul’s historical situation in mid-1C, this word is all but meaningless and irrelevant to modern Christians. However, if we take note of Paul’s history, situation, and characteristics, then a striking fact emerges: the reference to Athens follows hard on the heels of the reference to Satan. This, and the mention of hope in the verse between, prompts the question: Did Athens put the fear of Satan into Paul? Consider Paul’s action in sending Timothy back to Thessalonika "for fear that somehow the Tempter had tempted you, and all our work would be in vain" (1T.3:5d / Prophet Version). All this suggests that Athens is the material cause of Letter A, and even its place of composition: "Most likely the letter [ie. what we call A] was sent from Athens or Corinth about the year A.D. 51" (CBC 8; 11).

With Paul, every word is to be defined and interpreted by reference to its placement within the verse, and its immediate relation to all the other words therein; and by reference to the larger context (passage, chapter, letter), and to the wider historical situation around Paul, and within the Roman Empire at mid-1C. Failure to take all of these things into account will usually lead to confusion and error; as this essay hopes to demonstrate.

4. Emergent Traditions & the Prophet-Version

This essay is built around the idea that the Christian religion and the Christian churches have always taken a variety of forms expressed through many lines of ‘tradition’. This was also the case in the most pivotal years of Church history; the first two decades following Christ’s Death and Resurrection. At this time, one of the most important lines was the Persecution-tradition of the Jewish-Hellenist Christians that was, in some ways, the driving force behind the emergence of the Jewish-Hellenist Christian tradition that led directly to the Gentile (ie. Greek Catholic) Church and its collection, use, modification, and distribution of Paul's letters.

The Christianity, and its Greek-language prophetic literature, that emerged so decisively in the second and third centuries was the basis of the MSS and folios of the fourth and fifth centuries; which are - in turn - the main sources of the best modern versions of the Holy Bible. During the four centuries or so that the 27 books traveled down the road of liturgical composition, transmission, collection, arrangment, and reproduction, the pristine forms of the original MMS had long since faded from view. Of course, this had no real bearing on the Church of that period (ie. they were largely unaware of the many minor, and few major, textual changes), but today scholars are in a better position to work their way back to something approaching these primitive forms of the original autographs. (Although some may doubt the value of this project, and its achievements, others are more concerned to test everything, hold fast to what is good, and apply it to catechetical, liturgical and evangelical goals.) Since 1&2 Thessalonians are widely achnowledged to be the earliest books of the New Testament, they are our best witness to the particulars of the early Jewish-Hellenist proto-christian persecution-tradition line that led - more or less directly - to the creation of a new religion. From out of the trials and tribulations of Judaism emerged a firey form of early Christianity.

If one were inclined to more effectively evangelize the world, one way to begin might be the publication of a version of the New Testament that is ordered according to reason and history, rather than sentiment and long ingrained habit. A sequence of the 27 books based on their dates of composition would have many advantages over the current (haphazard) arrangement. For example: Luke’s Gospel and Acts would be treated as a single unit (ie. presented ‘back to back’); Mark’s gospel would come before everything else (except Paul); 1John would preface John’s gospel; and all of Paul’s genuine letters would be clearly distinguished from the deutero-pauline literature. Also, later interpolations (eg. Rom 13:1-7 and 16:25--27) would be removed from the letters, and placed together elsewhere (eg. Book of Additions), or footnoted. All of these editorial innovations would greatly enhance the readability and intelligibility of the New Testament for a new generation!

Let us now imagine that we have a copy of just such a revised version of the Bible before us now. Our hypothetical historically ordered copy of the New Testament is called the Prophet Version (aka PV). Turning to page one, the first words to greet us are Paul’s wordy thanksgiving, the gist of which is simply put: We give thanks to God that you accepted the word of God (cf. 1T.2:13). A better opening for the New Testament would be hard to imagine. However, after this we immediately run into a highly bothersome passage that many Christians think is something of an embarrassment (to say the least). This is the politically incorrect so-called 'anti-Jewish polemic' in v.14-16. Not at all the sort of thing one would wish to see on the first page of the New Testament! And yet there may be hidden treasures lurking between the lines ...

Given the importance of Paul’s words, it should come as no surprise that proper punctuation is also essential to a good translation. Of the available versions, only some editions of the NAB omit the infamous “anti-Jewish comma” and end verse 1T.2:15a with a period. Both of these items help to make Paul’s meaning clearer. Indeed, it is entirely possible that the anti-Jewish comma is, in part, a result of a misreading of v.15a of the anti-Jewish polemic. Yes, with Paul, every dot, every comma, and every iota actually matters!

5. THE PROBLEM WITH LUKE

Because of the historical discrepancies (between the accounts of various key events) in Paul and Luke, some scholars (eg. Hengel) conclude that Luke had no knowledge of Paul's epistles. But just consider how very unlikely such a possibility really is. By c.110CE, when Luke was finishing up his two-part book, over 45 years had passed since Paul's demise (c.63). By then the letters had been collected and were circulating all around the Mediterranean Basin. Luke could hardly be ignorant of such an important development among the various Gentile churches; especially in light of his great interest in the man. In fact, there is plenty of evidence in Acts that Luke used (at least some of) Paul s letters as a source (eg. the basket escape from Damascus). The reason why there are so many inconsistencies and contradictions between Luke and Paul is that Luke was not writing a factual biography of Paul, but rather only used those pauline materials that could be of value to his 'theological history' of the early Church.

Despite M.Hengel's exuberant advocacy of the value of Luke's history of early Christianity, we feel that Lukan insertions are generally ill-advised when one is supposedly studying Paul. Certainly Luke's account of Paul's experience in Athens bears no resemblance whatsoever to what actually happened to Paul, Silvanus and Timothy when they stopped over there during their fearful flight across Greece. Hengel also argues that Paul was well versed in Hebrew, and based on Luke's account this is perfectly feasible; but Paul himself says nothing whatsoever to support this idea. Hengel seems to assume that being a zealous Pharisee necessarily implies some fluency in the Hebrew language; but all the evidence suggests that a Greek speaking Pharisee would be more motivated to be zealous than his Aramaic counterparts (especially in Judea). Moreover, knowledge of Hebrew - or Aramaic for that matter - is hardly necessary to study with rabbi's, nor is it required in order to persecute the radical Greek-speaking 'blasphemers'.

This is only a minor example of how even a minimal use of Lukan material can adversely affect Pauline studies. A far more serious example is the image of 'Saul the killer-Pharisee', which is based on a potent combination of verses culled from both Luke's and Paul's writings. The consequences of this unfounded and common misperception of Paul is dramatically illustrated by Hoth's version of Acts, where Paul is quietly observing the stoning of Stephen, and is made to say the following remark: "Any man who follows Jesus deserves to die" (Hoth 685). We dare to suggest that such words never came from the lips of Paulos! No matter how 'violent' Paul's persecution of the Hellenist 'followers of Jesus' in Palestine may have been, we hardly think it included illegal, unethical, and barbaric actions such as mass murder! Indeed, the very suggestion indicates a grave ignorance of the sources of Paul's 'Christian' ethics.

Another problem with modern Pauline studies is that this area of biblical scholarship is severely hampered by a serious lack of methodological rigor. This is most evident in the widespread use of Luke's 'Acts' as a secondary source (which is usually treated as a primary source). Although some are more cautious in their use of Lukan materials than others; we nevertheless suggest that any admittance of any secondary sources during the initial study of the primary sources is an unjustified violation of methodological first principles, which state that ALL our attention must first be focused exclusively on Paul's genuine letters. Since the use of Acts as a historical source is inherently problematic anyway, and would inevitably force us to don 'Lukan Lenses' (thus leading to a distorted and biased view of Paul), we can only conclude that the use *any* non-pauline literature (ie. post-6OCE) is more of a hindrance than a help, and can just as often lead to confusion and misunderstanding as to clarification. A vigorous application of Occams Razor demands that scholars remove their Lukan Lenses, for foreign sources are neither required nor wanted at the all important first stage of study.

6. What Aren't They Saying About Paul?

In his popular book on Paul, Plevnik begins with a detailed examination of 'Paul's Damascus Experience'. He starts the opening chapter with the following remark: "Paul's life as a Christian and his apostolic ministry began, according to him, and as recounted in Acts, at his encounter with Jesus at Damascus" (Plev 5). Now there are a couple of things wrong with this statement. From the methodological point of view, the most serious error, by far, is the false statement of 'fact' contained in the phrase "according to him". We call it false because there is no reference to such a meeting in any of Paul's genuine letters. [Gal 1:17 can only support the idea if we make the simple word 'returned' bear the weight of a mountain by inserting the entire Lukan story into these eight letters. Not even the author of this essay could be comfortable with a word that is so amazingly top-heavy!]

The reason this pertinent fact is overlooked is owing to the general confusion among scholars about everything regarding Damascus. This city is not treated like all other cities! Moreover, the scholars routinely treat Acts as a core member of Paul's genuine letters. This gross methodological blunder is staggering in its negative consequences, and a sure indication of sloppy thinking among the otherwise clear-headed experts on Paul. The plain fact of the matter is that inserting Luke into Paul is like mixing grapes with pumpkins! There is simply no excuse for a supposedly scientific exegesis of Paul's letters to wantonly mix and match these biblical 'grapes and pumpkins' as if the obvious differences between them were of no significance whatsoever!

By following this irrational and piously traditional 'method', what the scholars do, albeit unconsciously for the most part, is to give more credit to Luke than is due (from the historical-critical viewpoint), and not enough to Paul. Whatever the merits of the Luke/Paul comparison may or may not be, such a project should only begin well after we give our undivided attention to Paul! This means we must pay full attention to the pauline texts, with as little reference to any and all future documents, ideas, interpreters, events, etc. as possible. The scholars should not be afraid to let Paul speak for himself, at least as far as his own life goes; after all, who is better qualified to address such matters, Luke or Paul?

7. METHODOLOGICAL RESPECT

Accordingly, this essay is also based upon an abounding respect for the authentic Pauline texts! What this means methodologically is primarily these three things:1. That we pay attention to what Paul is actually saying (this is something that theA good example of this traditional Pauline scholarship is the treatment accorded 2Cor 12:1-4, where all the scholars say that Paul is talking about himself in the third person (which is something that they acknowledge that Paul never does! cf.NJBC). The scholars are so willing to forget rules 1 and 3 here, because if they admit the obvious (ie. that Paul is talking about someone else), then straight-away they would have to admit their ignorance about who Paul is really referring to. Rather than do that, they are more than happy to overlook the three clues to the man s identity that Paul provides us: (1) he is a super-apostle (vii); (2) it was '14 years ago'; (3) the passage comes immediately after the reference to the basket-escape from Damascus. If these clues are not suggestive enough, there are more clues elsewhere in Paul's letters; but, of course, these can only be found by those who strictly adhere to ALL of the rules demanded by methodological respect!

NT scholars do NOT always adhere to).2. That we refrain from importing foreign material into the text. [It is astonishing how

often the scholars import Luke into Paul without warning or even acknowledgment.

Indeed, they usually treat 'Acts' *AS IF* it were one of Paul's genuine epistles!]3. That we believe that Paul *usually* (ie. almost always) says what he means, and

means what he says! Here again the scholars do not consistently follow this 'rule',

and are perfectly willing to do violence to Paul whenever and wherever they feel it

is theologically justified (ie. they value 'good theology' over 'good history').In sum, it is apparent that respect for Paul is essential to any good methodology, and that when this respect is conveniently misplaced, or temporarily set aside in order to better accord with our cherished notions and theologies, then violence to Paul is unavoidable, and ignorance and confusion the inevitable result! On the other hand, it is astonishing what we can learn from Paul when we let him speak for himself without trying to impose later ideas and assumptions that inevitably dictate what Paul "really meant" by this or that word, phrase, or verse.

8. Intro to textman's Reconstruction & the Wrath

Reading 1&2 Thessalonians in their current canonical configuration only invites confusion and misinterpretation; as the scolarly debates on authenticity, interpolation, dating etc etc so clearly demonstrates. Thus if we wish to gain a better understanding of the Thessalonian letters, it is imperative that the first order of business is to restore them to something like unto their original forms and chronological sequence. Then, and only then, can a prayerful and scientific exegesis of the epistles begin that relates the contents to the thinking of both Paulos and Silvanus, and to the larger historical situation prevailing in Greece, Asia Minor, and Palestine at mid-1C.

In his outstanding commentary, Wanamaker gathers the reasons against 'Schmithals' Compilation Hypothesis' and elects to support them; although none of these appear to be conclusive, or even very convincing! He also fails to note that the Philippian and Corinthian collections, as well as the 'primitive' forms of the Thessalonian letters, reduce the force of all these arguments to nil. But the justified rejection of Schmithals' reconstruction of the content and sequence of the Thessalonian letters is based on the valid observation that his "letters make little or no sense historically or rhetorically..." (Wan 55). While I agree with this conclusion, I take serious objection with the unwarranted assumption that Schmithals' basic insight must therefore be false. On the contrary, the insight is sound; what is required is not to jettison 'the four letters' scheme, but to so arrange them that they do make sense, both historically and rhetorically!

Incidentally, you may notice that the outline above this essay emphasizes the theme of God's wrath. It is a theme intimately bound up with the central concerns of the letters: persecution, judgment, 'the Day of the Lord', idleness, etc. It is also a topic that quickly gained a strong showing in the New Testament's earliest documents. For example, the tradition begun by Silavanus' and Paul's commentaries on the Wrath in 1&2Thessalonians was continued well into the second century. In 'Romans', which is easily the most interpolated of all Paul's letters, we find a post-Paul pauline commentary inserted immediately after a verse wherein Paul mentions the Wrath: "For the Wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of men who by their wickedness suppress the truth" (Rom 1:18 / RSV).

The following commentary runs from 1:19 to 2:11 inclusive. Yet Paul's commentary on the Wrath (Romans version) runs smoothly from 1:18, jumps around the non-Paul text, to 2:12-16. Reading Paul this way makes Paul's thinking far more intelligible and consistent with his thinking in the Thessalonian letters a decade earlier. Indeed, it makes even more sense when deliberately compared with his earlier commentary in Letter D, rather than with the 2C pious-insertion-from-the-margins!

9. FOUR VERSIONS OF 1T.2:13-16

The Reader is offered these four versions of the first words of the NT for comparison and edification. These are all popular and good translations for both casual reading and in-depth study. Be advised, however, that the JB (and the NJB) are English translations of the original French version, and is very free with its translating methodology (ie. it is a 'paraphrase Bible'). The Reader should also take careful note of verse 15a&b, which is easily the most interesting and important statement in the entire Thessalonian correspondance.

(13) Another reason why we constantly thank God for you is that as soon as you heard the message that we brought you as God's message, you accepted it for what it really is, God's message and not some human thinking; and it is still a living power among you who believe it. (14) For you, my brothers, have been like the churches of God in Christ Jesus which are in Judaea, in suffering the same treatment from your own countrymen as they have suffered from the Jews, (15) the people who put the Lord Jesus to death, and the prophets too. And now they have been persecuting us, and acting in a way that cannot please God and makes them the enemies of the whole human race, (16) because they are hindering us from preaching to the pagans and trying to save them. They never stop trying to finish off the sins they have begun, but retribution is overtaking them at last.

(13) ... the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as what it really is, the word of God, which is at work in you believers. (14) For you, brethren, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus which are in Judea; for you suffered the same things from your own countrymen as they did from the Jews, (15) who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all men (16) by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles that they may be saved-so as always to fill up the measure of their sins. But God's wrath has come upon them at last!

(14) Brothers, you have been made like the churches of God in Judea which are in Christ Jesus. You suffered the same treatment from your fellow countrymen as they did from the Jews (15) who killed the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and persecuted us. Displeasing to God and hostile to all mankind, (16) they try to keep us from preaching salvation to the Gentiles. All this time they have been "filling up their quota of sins," but the wrath has descended upon them at last.

(13) ... accepted it not as the word of men, but as it actually is, the word of God, which is at work in you who believe. (14) For you, brothers, became imitators of God's churches in Judea, which are in Christ Jesus: You suffered from your own countrymen the same things those churches suffered from the Jews, (15) who killed the Lord Jesus and the prophets and also drove us out. They displease God and are hostile to all men (16) in their effort to keep us from speaking to the Gentiles so that they may be saved. In this way they always heap up their sins to the limit. The wrath of God has come upon them at last.

10. WHAT CAN BE LEARNED FROM A MAP?

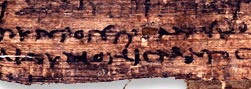

The answer is, of course, that it depends entirely on the *quality* of the map. Some maps are better than others. The one shown below is a rather simple map of the Mediterranean Basin entitled 'The World of Paul'. It can be found in several of the books from the popular Catholic biblical commentary series, the Collegeville Bible Commentary from the Liturgical Press. This one is from CBC#8 by Havener, pages 56-57. Actually, the map in the commentaries is slightly larger than the portion shown below; it also shows Rome to the west of Macedonia. I have also modified the map somewhat by adding three items of my own: (1) Inserted 'Antioch' below Seleucia; and added the arrow pointing to the East. (2) Inserted 'Petra' to the SW of Jerusalem. (3) Added 'Major Gap Here?' pointing to the non-existent city of Alexandria to show that, for pauline scholars, the African portion of the Empire (including Egypt) is gone! Now these errors of omission are by no means minor, and I would ask the Reader to reflect carefully on the bias and sloppy scholarship that these omissions indicate.

![the world of paul [map]](map1.gif)

Let us now briefly examine some of the particulars involved in the thinking that lies behind this map; 'behind the scenes' as it were. First of all, and the most obvious error by far, is the inclusion of the city of Tarsus in the province of Cilicia. The reason that is an error is that this item is a Lukan importation. There is no evidence for Tarsus in Paul's own writings! In the same way, there is no evidence in Paul for the famous 'Road to Damasus' conversion incident. And none for Petra either; ie. it is a supposition drawn from the one word 'Arabia' that Paul used. As to the serious omission of Alexandria: it was not only a very important center for Jews in the Diaspora (ie. outside Palestine), but it was the second city of the Empire, and it is unlikely that Paul did not go there at least once in his adult years. So then, observe Gal 1:17 ... "I did not go up to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before I was. Instead, I went immediately into Arabia, and later returned to Damascus."In this mere handful of words, Paul summarizes two to three years of his early life as a Christian (c.37-39). Paul's obscurity about this period in his life following the expulsion of the Jewish-Hellenist Christians from Jerusalem is obviously intentional, and one might say almost too deliberate. Now the scholars admit that some of these Greek-speaking Jerusalem refugees went north to settle in Galilee and Antioch, but they are curiously reluctant to accept the idea that other refugees (with Paul among them) went south-west to Egypt and Alexandria, although the large Jewish community (including Philo) within that great city would be an ideal safe-haven for the fleeing refugees. Yes, the scholars would much rather pretend that the earliest Christians were utterly ignorant of the city of Alexandria up until the tail-end of the second century ...

Even though there is evidence in the New Testament contrary to this absurd assumption [4X:see Acts18:24 for Apollos of Alexandria; while Paul does make mention of Apollos (eg. at 1Cor 3:4-6) he nowhere mentions Alexandria directly.] This supposed nonexistence of Alexandria within the early Christian world is yet another example of how scholars and theologians ignore and bypass the textual evidence in favor of their own arrogant assumptions of how church history MUST HAVE unfolded.

Once again history is made subservient to theology and the grand illusion of an Alexandria-free Empire! But Paul could hardly be ignorant of the 'Greatest City in the World', the second city of the Empire, even if he never went there. So the question is: What major city near the Great Sea, not far from Palestine, and south of Judea did Paul go to in c.38CE? Remember that Paul likes to stay close to the Great Sea, and away from Judea. He also likes to stay in important cities (major seaports, provincial capitals, etc). Paul is most comfortable in Asia Minor (eg. Ephesus); ie. far from Alexandria and Jerusalem, but close to his churches to the east (Macedonia) and to the west (Galatia).